by Saashya Rodrigo, Ph.D & Amelia S. Malone, Ph.D

National Center for Learning Disabilities

Please note that this content is best viewed on a tablet or computer.

Contents

The Challenge

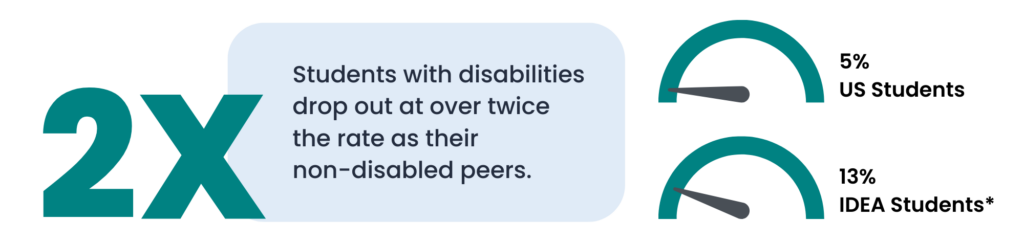

Students with disabilities graduate at lower rates than their nondisabled peers. Of the 49.4 million public-school students in the U.S., 13% receive services under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act1 (IDEA; U.S. Department of Education, 2022), a law that provides a free and appropriate public education to children with disabilities2 ages 3–21.

There are many reasons students drop out of high school, and it is often a combination of factors. One of the most common reasons is a need for more engagement or interest in school. If students do not feel connected to what they are learning or struggle to learn, they may become disengaged and lose motivation. Another factor is learning challenges, such as an identified specific learning disability or a lack of support at home. With the necessary resources and support, these challenges can become manageable and lead to staying in school. Addressing the underlying causes of dropout rates and providing targeted support to help students stay engaged and succeed in school is important.

Disability is one of many risk factors for dropping out of high school. The intersection of disability, race/ethnicity, and poverty puts high-school students at a higher risk of dropping out.3 Disciplinary exclusion, another dropout risk factor, is more common among students from historically marginalized backgrounds.

Disciplinary exclusion, another dropout risk factor, is more common among students from historically marginalized backgrounds.

Students with disabilities are more than twice as likely to receive out-of-school suspensions than their nondisabled peers.4 Students of color are disciplined and suspended at higher rates than their white peers.5,6

Students with specific learning disabilities9 can learn on par with their nondisabled peers if given the appropriate instructional resources and support.10 Nevertheless, 12% of students with specific learning disabilities drop out of high school.

What factors predict graduation rates for students with specific learning disabilities?

- Disciplinary exclusion,

- Lower-than-average grades,

- Repeating a grade,

- Low parent expectations, and

- Poor quality of relationships within schools

Research suggests these factors are significant predictors over and above sociodemographic indicators such as race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status.11,12

A shift must occur within the education system to ensure all students with disabilities receive adequate academic, behavioral, and emotional support on their path to graduation and beyond. The first step in this process is ensuring a supportive framework is in place to track student progress, use data and student assets to target gaps, and individualize support as needed. A comprehensive supportive framework ensures all students can access quality high-school course content in an environment that promotes and enables their agency, belongingness, and school connectedness while accounting for their individual experiences, struggles, and celebrations.

A Comprehensive Supportive Framework to Promote Graduation and Postsecondary Success

The best way to prevent learning, behavioral, and health challenges is to continuously assess progress and take action when data suggests there may be risk for adverse outcomes. Early intervention, like medicine, is the most effective way to ameliorate future challenges. The first step in mobilizing a comprehensive early intervention system is understanding how existing conceptualizations can be brought together and built upon to ensure students thrive.

To mobilize efficient access to resources and support, a multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) builds a foundation by which schools can equitably allocate services to students to promote success. This system evolved from tiered public health models that use data-based decision-making to provide services commensurate with risk for adverse outcomes.

MTSS, in its most evolved form, tracks academic, behavioral, and well-being data across all students to determine who needs more targeted or intensive support at any given time. Educator teams use progress-monitoring data to intensify and individualize instruction and support as needed. Often conceptualized as a three-tiered model with increasing intensity at each tier, all students receive universal support (high-quality, evidence-based instruction). Suppose data indicate a student needs more support than received in the general education classroom. In that case, they may receive targeted (Tier 2) or intensive (Tier 3) support in small groups or one-on-one, depending on their needs.

Foundational to this model is ensuring everyone receives the services they need when needed. Some students may require more targeted support for a short or longer period (often delivered in small groups). A few students may require more intensive support for a longer period (often delivered individually).

Current research efforts (e.g., I-MTSS) focus on effectively and efficiently scaling up data-based decision-making and integrating evidence-based practices across academic, behavioral, and well-being metrics for students with and at risk for disabilities. This integrated approach is challenging but ensures that the most marginalized students have access to what they need when they need it to succeed.

According to the framework, a healthy integrated system of supports includes the following:

- Integrated continuum of research-informed practices

- Comprehensive data-driven decision-making

- Integrated teaming and coaching structures

- Integrated professional development

- Additional systems to support sustained and scaled implementation

Much of the research on MTSS is at the elementary and middle school level. Implementing MTSS in high school poses challenges, as there are vast changes to scheduling, course requirements, data mobilization, and implementation constraints.

As students progress to middle and high school, the support provided should become more refined and individualized. Because of contextual constraints, researchers identified a set of monitoring metrics that could help determine whether students are on track to graduate high school. Student attendance, behavior, and course grades significantly predict whether a student graduates.13 Layering “ABC” data-monitoring procedures simultaneously assess MTSS and allow decision-makers to mobilize resources for at-risk students.

Critical to successful MTSS implementation in high school is monitoring student attendance, behavior, and course grades as a proxy for the risk of dropping out of high school. Chronic absenteeism (defined as missing 10% or more of school) correlates with dropout rates, and students with disabilities are at an increased risk of being chronically absent.14 Chronic absenteeism has an additive effect on student learning. Students can only engage with content if they are physically at school. Behavioral challenges (including out-of-school suspensions, office referrals, and disciplinary actions) grade retention, and one or more course failures (especially high-stakes courses such as Algebra 1 and English 1) grades also increase student risk for dropout.15,16

These data “ABCs” are a quick way for schools to assess the health of MTSS. They serve as an “early warning system” (EWS), much like a thermometer can indicate an individual has an underlying problem. However, a fever does not describe the source of the systemic problem. Teams must drill down, find the challenge’s source, and designate resources to meet students’ needs.

Monitoring these metrics and integrating intentional programming that teaches academic skills and fosters school connectedness helps schools ensure that students with disabilities receive appropriate instruction and support commensurate with their needs.17

Student success systems emerged from research on the effective implementation of MTSS and EWS for improving graduation rates. Student success systems attempt to integrate components of these models while also expanding the scope to include mindset and factors affecting students outside of school to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of existing frameworks. A key challenge in the successful implementation of a comprehensive support framework is ensuring that they consider the following:

- Supportive community relationships

- Holistic- real-time- actionable data

- Response and improvement system

- A shared set of mindsets

Key to a robust student success system is a unified data-tracking system that cohesively monitors the existing comprehensive system of support and relies upon holistic, real-time, actionable data (the attendance, behavior, and course grades “ABC’s”); supportive community relationships; dedication to continuous improvement (e.g., understanding next steps when a student is at risk); and a shared set of mindsets that all students can succeed. An effective student success system allows schools to consider whether students are developing agency, belongingness, and connectedness (the little “abc’s”) on their path to graduation. Combining these features builds a system of supports that considers student context related to their performance and struggles in high school.

Understanding What Students with Disabilities Need to Be Successful

While research suggests that robust implementation of MTSS and EWS can positively impact graduation rates, there is a long way to go to ensure universal implementation and effective resource deployment. The GRAD Partnership for Student Success—a coalition of nine organizations—seeks to improve graduation outcomes and postsecondary success for historically marginalized populations by refining and scaling up student success systems nationwide.

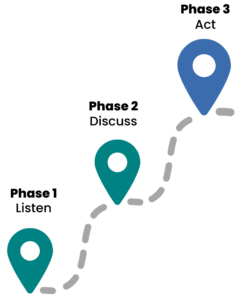

To better understand the barriers to implementing a unified student success system that integrates, extends, and increases the capacity of existing student support efforts, the National Center for Learning Disabilities (NCLD), one of the nine partner organizations, led a two-phase inquiry with educators and administrators, individuals with learning disabilities, and experts in the field of special education.

The two-phase inquiry focuses on understanding how people interpret the language around student success systems and how they perceive these systems to benefit or inhibit efforts to keep students with disabilities on track to graduate and succeed after high school. NCLD wanted to know if participants could envision a support system that adequately addressed the needs of students with specific learning disabilities.18 Listening and understanding uncover areas for action for implementing high-quality student success systems focused on improving student outcomes.

In the first phase, NCLD conducted three focus group sessions with researchers, special education administrators, and young adults with learning disabilities on their perceptions of student success systems. Three key themes emerged from the sessions:

- Change mindsets at the school, district, and state levels with shared values rooted in equity. Data-based conversations must center on the most vulnerable students.

- Take early action to change the trajectory for students. Taking action on at-risk data in high school is often too late. Early identification and intervention are key to success.

- Foster inclusive conversations to build cross-collaborative partnerships with students, families, educators, school counselors, social workers, and other parties, to collectively track goals and data, and build successful transition planning for students with disabilities.

Participants highlighted the need to center students in the conversation to empower them to advocate for themselves and share their goals and aspirations during transition planning. Including student and family voices breaks down barriers and places value on their needs, thoughts, and desires.

In the second phase (described here), NCLD hosted a convening in New Orleans in February 2023 with educators and administrators, young adults with learning disabilities, caregivers of students with learning disabilities, disability advocates, and experts in the field of special education to dive deeper into the barriers to success in high school for students with disabilities. These discussions occurred to build a set of actionable next steps to build a more supportive system with students with disabilities at the center of the conversation. NCLD was interested in hearing collective lived experiences from multiple viewpoints to build a consensus around the necessary components of sustaining a successful comprehensive system of supports among high school students with disabilities.

The discussion focused on barriers related to systems, people, and knowledge:

- Mindsets: How do we develop shared mindsets to ensure key decision-makers work together to support students with disabilities on the road to high school graduation and postsecondary success?

- Building Knowledge: What is the knowledge required to successfully support students with disabilities on the road to high school graduation and postsecondary success?

- Systems: How can we make structural changes to existing frameworks to better support students with disabilities on their road to high school graduation and postsecondary success?

This two-phase inquiry attempts to build a collective conversation with students with disabilities at the center to identify key areas for action as we think critically about the best ways to support students with disabilities on their path to graduation and beyond .

NCLD relied on live polling data using Slido and designated notetakers to gather information on participants’ perceptions. NCLD assigned the 64 participants to 10 tables, ensuring each table had at least one representative from each constituent group (educator, young adult, caregiver, expert). There were fewer than ten young adults and caregivers, so at least one representative from each group sat at the table.

NCLD staff designed all content in collaboration with members of our Professional Advisory Board (leaders in the field in supporting students with disabilities within a comprehensive system of support), experts in the field of special education (content areas included transition planning, multi-tiered system of support implementation, early warning system implementation, disability intervention, data-based individualization), and members of the GRAD Partnership.

The meeting consisted of two sections. First, participants explored current trends and issues in supporting students with disabilities on their path to graduation. NCLD shared national graduation rates and results from the first phase of inquiry (focus group sessions). Participants brainstormed solutions for why students with disabilities are not graduating from high school at the same rates as their non-disabled peers. Analyzing these data indicated that unsupportive systems, stagnant mindsets, and insufficient action hinder success.

Next, participants examined effective systems to improve graduation rates before completing a group activity—collectively examining a case study delving into the metrics that matter for improving graduation rates for students with disabilities. Finally, these activities allowed participants to address the identified barriers by discussing pathways to success—these pathways to success work to refine an innovative system of support to improve graduation rates.

Of those who work in schools (e.g., educators, administrators) or recently graduated high school (young adults with learning disabilities), over 75% reported that their high school informs students when they are not on track to graduate high school. They then indicated that support for students with disabilities who were not on track to graduate was poor. Considering students with disabilities, they ranked the importance of a variety of risk factors for determining student success (in rank order):

- Attendance

- Course grades

- Student mindset

- Health, wellbeing, & belongingness

- Academic supports

- Teacher mindset

- External supports (e.g., caregivers/families)

- Behavior

- School resources

The discussion around how to help students struggling in these areas uncovered multiple barriers that obstruct the pathway to graduation for students with disabilities. Discussion around roadblocks to success coalesced around three overarching themes: changing mindsets, building knowledge, and implementing effective systems.

Considerations for Phase 3 (Act): Removing Barriers to Pave the Way to Success

Mindsets must shift before individuals can obtain the knowledge to develop a holistic and effective system of supports to ensure students with disabilities succeed in high school and thrive after graduation. Without shifting mindsets toward the most vulnerable, overhauling existing systems will fail to drive success. The discussions generated pathways to address these barriers and pave the way to success. It is imperative to center students with disabilities’ needs in developing support systems.

Using a road as a metaphor for the pathway to high school graduation, many students with disabilities experience continuous roadblocks, creating a ravine of opportunity gaps. With these systemic barriers, students consistently detour and may spend so much time on the detours that they miss their opportunity to graduate—or they become so frustrated that they divert to another path altogether.

Shifting Mindsets

Barrier

Unrealistic Teacher Expectations

There must be a balance between the idealistic expectations we place on the shoulders of schools and teachers and the realities of what is possible, given staffing capacities, resources, and timelines. Barriers within the current educational climate, such as teacher staffing issues and the resulting focus on emergency hires, block the successful implementation of the ideal vision for what schools should do to improve student graduation rates. Expanding on this point, participants at the convening expressed concerns about the focus on filling teacherless classrooms with warm bodies rather than with skilled teachers in improved working conditions that promote job satisfaction and retention.

Currently, the requirements to be a teacher in the public school setting are quickly declining nationwide, with job openings expanding to those without a Bachelor’s degree or any education-related knowledge or skill. The growing turnover rates caused panic across the country, shifting efforts away from identifying ways to recruit and retain skilled teachers to softening the rigor of skill and knowledge needed to be an effective teacher just so that districts can fill vacancies. In addition, schools and teachers largely bear graduation and test-score-driven penalties, fostering a punishment model that further fuels the teacher turnover crisis and questions the purpose of learning outcomes.

The existing strategies address neither the teacher retention issue nor its outcome of helping students to get back on track to graduate. Without skilled teachers who are valued, respected, and well-supported in their classrooms, districts cannot expect students to succeed, no matter how well-designed the systems and processes in place may be. Simply said, most schools in this nation are under-staffed, under-supported, and under-resourced. Therefore, schools cannot keep up with the idealistic expectations in the name of student success while schools crumble at the foundational level.

Pave the Way to Success

Shift from Teacher Recruitment to Talent Acquisition

While teacher turnover may require an emergency solution, current emergency solutions (e.g., emergency hiring efforts that do not require applicants to have the necessary training) fail to address the core issue—the drastic decline in the number of skilled and experienced teachers remaining in the classroom. Teacher participants at the convening shared that teachers leave because of declining job satisfaction resulting from a lack of support, autonomy, and value. Filling in teacher vacancies with potentially unskilled, unqualified adults is not a feasible temporary fix, let alone a long-term solution. Participants expressed a need to shift the focus from “teacher recruitment” to “talent acquisition,” in which districts prioritize the quality of new hires rather than the quantity of new hires. Teachers’ job responsibilities, compensation, and support must reflect their value for this mindset shift and come to fruition.

Barrier

Tunnel Vision on Standardized Testing and College Readiness

Educators, young adults, and caregivers expressed a shared concern about the focus on state testing requirements and college readiness, emphasizing that these outcomes may not be ideal for all students, particularly those with disabilities. A diverse student population requires diverse options instead of a one-size-fits-all approach steered by test scores and college preparation. The current high school experience must consider alternative, less traditional paths centered on the diversity of student strengths and ambitions. The conversation needs to focus less on how students can fit into our ideas of success and more on understanding what success might look like for each student based on their unique strengths and experiences. The heavy focus on standardized testing and college readiness is not a student-centered pathway that promotes differentiated learning and outcomes, particularly for students with disabilities.

Pave the Way to Success

Support the Core Student Success Team

Successful implementation of a holistic system requires extensive support and resources. It is important to help teachers across areas of expertise understand how their beliefs and expectations of what students with disabilities can achieve affect student outcomes. Because an interventionist can only see a limited number of students daily, building-level mindsets must ensure that everyone embodies the notion that all students deserve to learn and succeed. However, more than shared growth mindsets is required to drive change. Educators require adequate time, resources, and team collaboration to develop a shared understanding of one another and shift their mindset toward a student-centered assets approach.

Similarly, to ensure many parents no longer feel isolated while working with the education team to develop an Individualized Education Program (IEP) for their child, a comprehensive system of supports must include resources and support from community organizations. Participants also suggested having internal support groups for each constituent (parent-led groups for parents, student-led groups for students, teacher-led groups for teachers). In addition to meeting regularly to discuss and problem-solve within individual groups, participants also suggested that groups convene collaboratively to share hurdles, perspectives, and adapt existing plans to accommodate new needs. In this manner, key players will feel supported at the individual level and work collectively to achieve the shared goal of promoting success for all. With a clear and relevant definition and purpose that reaches the complete span of learning and development, fidelity of implementation, and strong support for all key players, this comprehensive and ever-evolving system of supports collaboratively and proactively shifts student growth and success across all learning stages.

Barrier

Exclusionary Decision Making

Participants reported that a system of supports must operate within reality and reflect more on current trends and experiences to address the most pressing needs that students and educators face in classrooms today. Student and educator perspectives are often not included in the inception and design of systems and frameworks, making key constituents feel unheard. This lack of inclusivity in decision-making creates a perpetual feeling of implementing an under-supported and under-resourced model that can never meet student needs, maintaining the silos and disconnects across systems.

Similarly, to ensure many parents no longer feel isolated while working with the education team to develop an Individualized Education Program (IEP) for their child, a comprehensive system of supports must include resources and support from community organizations and internal support groups for each constituent. Participants suggested that these support groups (parent-led groups for parents, student-led groups for students, teacher-led groups for teachers) meet regularly to openly discuss and problem-solve. Participants also suggested that all parties convene periodically to share hurdles and perspectives to adapt existing plans to accommodate new needs.

In this manner, key players will feel supported at the individual level and work collectively to achieve the shared goal of promoting success for all. With a clear and relevant definition and purpose that reaches the complete span of learning and development, fidelity of implementation, and strong support for all key players, this comprehensive and ever-evolving system of supports collaboratively and proactively shifts student growth and success across all learning stages.

Pave the Way to Success

Collaborate, Communicate & Re-Conceptualize

Given the existing silos between key players, participants proposed improving collaborations that are grounded in open communication. Participants shared their thoughts on dismantling the hierarchical system in which caregivers and students are at the bottom of the decision-making tree. Instead, given that each key player shares the same goal (to see the student succeed), participants highlighted the benefit of intentional and continuous collaboration in the design, implementation, and adaptation of systems and processes. For example, the IEP process must consider each constituent’s level of understanding to ensure program development includes all voices and is not prescriptive. Participants suggested establishing a Student Success Board, in which diverse professionals (e.g., school faculty and staff, school counselor, and education experts) review IEPs and learning goals while working collaboratively with students and their families to better understand their perspectives. These collaborative conversations can help prioritize student strengths and gaps to build a program that includes evidence-based practices suited to meet the student’s goals and needs.

Collaboration and communication among key players may reveal the need to re-evaluate and re-conceptualize the high school experience. Not every student thrives in the status quo high school environment. Some students may need a more personalized path to graduation that includes a flexible course plan with a flexible graduation date to accommodate. It is equally important to consider that college may not be the only postsecondary pathway for some students. Educators shared that alternative post-secondary pathways, such as vocational school, community college, the military, or employment, should be included in the transition plan conversation. This mindset shift highlights the need for high school curriculum to include more hands-on, real-world experiences at the course and extracurricular levels, including internships and fellowships. Students’ pathways to success should look different. Values within the education system must shift to include alternative routes to ensure all students receive appropriate transition experiences and thrive after high school.

Barrier

Deficit Mindset

Disability stigma pervades society. Unfortunately, societal norms still trend toward a deficit mindset for individuals with disabilities, often creating a roadblock to accessing appropriate services and support. Special educators reported that administrators and general education teachers consistently set low expectations for students with disabilities, focusing more on what they cannot do than their strengths. Young adults with disabilities echoed these sentiments. They shared personal stories of frustration—of being perceived as less capable than their general education peers based on how teachers treated them. This reality obstructs closing the opportunity gap between students with disabilities and their nondisabled peers.

Pave the Way to Success

Growth Mindset

At the core of a flourishing support system are key players who are skilled, driven, and lead with a strengths-based mindset. While there is value in understanding barriers to success and challenges that slow down or inhibit progress, it is equally important to identify how to build upon strengths to work toward progress. Building upon strengths is the nucleus of a growth mindset, imperative for driving positive change. Shifting mindsets is challenging and requires a crack in cultural norms. Educators and leaders must internalize a growth mindset and ensure students learn to lean on their strengths in their most formative years, especially as they learn to advocate for their needs related to support and accommodations.

Building Knowledge

Barrier

Inadequate Teacher Preparation

Many participants reported that educator preparation programs are not transparent about the real classroom experience and what is required to provide targeted and intensive academic and behavioral support to students experiencing gaps in learning. There is a persistent disconnect between knowledge and practice. Educators reported having a negative perception of professional development because training is not consistent, realistic, inclusive, or engaging. Resources (e.g., time, substitute teachers) are scarce and do not allow for deep learning.

Often, schools and districts collect data on student progress. However, administrators and educators lack the knowledge and skills to effectively analyze these data to make informed decisions to improve student performance. Although educators may be able to identify learning gaps, they sometimes lack the skills to use data to identify and implement appropriate instructional change to fill those gaps. By high school, the ravine of missed opportunities widens and deepens, and teachers cannot simultaneously teach prerequisite skills alongside more rigorous grade-level content.

Teachers also reported a pervasive knowledge gap between general and special educators. General educators often are not trained on disability identification, disability law, or IEP processes and implementation. Special educators explained that these perceived gaps seem wider in high school because of the following:

- instructors are content-specific,

- individual teachers do not follow students across classes, and

- there is no strategic consistency across course progression and course planning.

Students do not receive consistent, evidence-based instruction for improving reading, math, behavioral, and social-emotional skills as they move from one teacher to another throughout the day. The special education teacher cannot effectively bridge knowledge gaps across content areas in highly specialized classes while improving foundational skills.

Additionally, these teacher-level knowledge gaps hinder teachers’ abilities to identify and implement specific instructional strategies that target students’ needs. Instead, many teachers rely solely on mandated accommodations (e.g., extra time on an assessment). Many times, accommodations are insufficient for improving student performance. Strategic instructional modification is needed to bridge student learning gaps. Assessments, evaluations, and overall data system utility drive effective and targeted instructional modification, but have instead have become a checkbox item on the ever-growing list of legal compliance tasks.

Pave the Way to Success

Targeted and Pragmatic Pre-Service Preparation and Professional Development

Educators must acquire the knowledge and skills to effectively use data to group and intervene with students to bridge foundational skill gaps. Educator preparation programs and professional development must focus on how to take action based on student performance data and how to choose evidence-based practices accordingly. Educators reported needing time, support, and resources to learn, practice, and master skills learned during professional development sessions. Experienced experts must lead professional development sessions (e.g., with knowledge in MTSS, EWS, data-based decision-making, and Universal Design of Learning). They must be familiar with existing challenges in the classroom to ensure training considers reality rather than solely focusing on the ideal.

Barrier

Student Skill Gaps

Students’ skill gaps widen in high school. To make matters worse, students often do not know how to advocate for their needs. To graduate high school, students must complete the required credits and often pass a series of core courses (usually Algebra and English) and their corresponding exams. Exact graduation requirements vary by state. High school course content becomes vastly challenging, creating a widening abyss of gaps when there is no longer time to address foundational skills. For students with learning disabilities, the shift to high school often uncovers the snowball effect of these gaps. Scheduling constraints make it more challenging to provide consistent intervention and support. Students who struggle to decode words will experience roadblocks in accessing content across content areas if they do not receive appropriate interventions, support, and accommodations. Many high school educators do not have time to teach foundational skills (e.g., decoding, number sense) because they must maintain the scope and sequence of a challenging academic trajectory. Therefore, unaddressed knowledge gaps from elementary and middle school widen, and students cannot access content.

Pave the Way to Success

Speak Up, Act Now

Given the pervasive skill gaps many students with disabilities exhibit in high school, improving access to high-quality, evidence-based instruction is critical for success. General education teachers must learn to integrate high-quality, research-based instruction that is engaging and data-driven. If students do not adequately progress, instructional strategies, classroom groupings, or supports must change to meet their needs. Universal high-quality instruction is a foundational component of a healthy MTSS model and EWS monitoring system.

A healthy MTSS model also entails optimizing the use of Early Warning System data across all grade levels, highlighting the importance of early intervention to lessen or completely prevent the knowledge gap snowball effect.

While teachers are responsible for ensuring skill gaps do not persist, students must also have autonomy over their academic experience and become powerful self-advocates. Student success requires all parties to be on the same page. Students have a right to and need to understand their disability, where their strengths and skills gaps lie, and, given their experience, what accommodations help them compensate for gaps. Students with disabilities must be purposefully incorporated into IEP meetings, so they have a firm understanding of their performance data, available accommodations, and are trained on strategies to advocate for their needs within the classroom.

Barrier

Caregiver Knowledge Gaps

By law, caregivers must be included in the IEP development process. Often, they do not fully understand the breadth and depth of skills gaps, goals, available interventions, accommodations, and resources to advocate for their child’s needs effectively. It is not uncommon for parents to be unaware of the risks and challenges their child might encounter on their path to graduation. Sometimes, despite the evidence, requests for services and support are denied

Pave the Way to Success

Caregiver Education and Collaboration Efforts

To address knowledge gaps across teachers, students, and caregivers requires communication, continued education, and intentional advocacy efforts to ensure all parties understand the task at hand and can recommend viable solutions for fostering student success. All key parties must be involved in the IEP process from start to finish. Involvement should not be limited to compliance. Instead, the conversation and ambiance of the space must allow all participants to feel welcome, respected, included, and valued. Participants recommended developing a standardized IEP with accessible language to accommodate different levels of understanding across parties. Schools should assign an approachable and supportive central contact within the education team to ensure consistent, timely, and open communication across all parties.

Implementing Effective Systems

Barrier

Siloed Systems

Educators and researchers mentioned concerns that the existing supportive system fails for multiple reasons. Fundamentally, the system of supports is often poorly implemented or not designed feasibly within the constraints of the school system. Siloes pervade the system because data systems fail to communicate with each other and across schools. For example, progress monitoring systems may gather data on a different platform that does not sync with the student information system.

Additionally, data systems across districts and states vary greatly, creating confusion, inconsistency, and knowledge gaps among key players. The additional inconsistencies in progress monitoring and evaluation processes across states can lead to not identifying or misidentifying the root cause, resulting in mismatched interventions and missed opportunities for success. The overall systemic and operational lack of cohesion across schools, districts, and states also obstructs what should be a smooth and streamlined transition process for students advancing grade levels or moving schools. There are also no standardization metrics for preparing or storing IEPs, further complicating matters for students with disabilities.

Pave the Way to Success

Clarity, Consistency, and Purpose

Given the existing challenges with implementing an effective system of support that considers all students’ needs, there is an urgent need to rethink service delivery in collaboration with all key players, including the broader community. Processes must be consistent across schools, districts, and states, including a standardized plan for assessing implementation fidelity. Local context also matters, so this standardization process must also account for flexibility relevant to each school and district.

As many participants mentioned, using data and progress-monitoring tools to drive instruction should begin in the earlier grades, with continuation into the upper grades. There needs to be a clear connection between elementary, middle, and high school so services and support are not interrupted. Systems must be attached to the building students reside in, and not to the educator implementing them. That is, a system of supports must continue even if a building leader leaves their position, in order to prevent service gaps. High school educators should be trained to provide instruction on foundational skills in case students require intensive support. They must also understand the types of supportive accommodations students with disabilities need to be successful.

Additionally, data systems across districts and states vary greatly, creating confusion, inconsistency, and knowledge gaps among key players. The additional inconsistencies in progress monitoring and evaluation processes across states can lead to not identifying or misidentifying the root cause, resulting in mismatched interventions and missed opportunities for success. The overall systemic and operational lack of cohesion across schools, districts, and states also obstructs what should be a smooth and streamlined transition process for students advancing grade levels or moving schools. There are also no standardization metrics for preparing or storing IEPs, further complicating matters for students with disabilities.

Barrier

Inadequate Data Systems and Missed Opportunities

Districts across the country face more specific issues relating to data systems. Data systems are a tool that, when integrated effectively, provide demographic, academic, and behavioral information that key players use to understand the whole child better. Data systems support students at the individual, course, school, and district levels. Particularly for students with disabilities, data systems play an integral role in decision-making. However, many schools struggle to use data systems effectively and struggle to optimize the benefits of data-based decision-making. This roadblock is largely due to too many data management options, each utilizing different interfaces and procedures requiring varying user skill sets. Data management systems are also often not user-friendly, adaptable, and communicative with other data systems.

As many participants mentioned, using data and progress-monitoring tools to drive instruction should begin in the earlier grades, with continuation into the upper grades. There needs to be a clear connection between elementary, middle, and high school so services and support are not interrupted. Systems must be attached to the building students reside in, and not to the educator implementing them. That is, a system of supports must continue even if a building leader leaves their position, in order to prevent service gaps. High school educators should be trained to provide instruction on foundational skills in case students require intensive support. They must also understand the types of supportive accommodations students with disabilities need to be successful.

Additionally, data systems across districts and states vary greatly, creating confusion, inconsistency, and knowledge gaps among key players. The additional inconsistencies in progress monitoring and evaluation processes across states can lead to not identifying or misidentifying the root cause, resulting in mismatched interventions and missed opportunities for success. The overall systemic and operational lack of cohesion across schools, districts, and states also obstructs what should be a smooth and streamlined transition process for students advancing grade levels or moving schools. There are also no standardization metrics for preparing or storing IEPs, further complicating matters for students with disabilities.

Pave the Way to Success

User-Friendly, Purposeful, and Holistic Data System for All Constituents

A shared data management system that is designed and implemented with the educator, student, and parent in mind is an essential component of bridging silos and ensuring that all constituents can be on the same page. Expecting key players to learn how to manipulate multiple data management systems is ineffective. It is important to ensure that key players implement these data-management procedures and practices with purpose and actionable intent. Data collection and analysis should not serve as a compliance checkbox. Instead, the data management system should be the engine that powers high-quality data-based decision-making.

Barrier

Inconsistent and Unclear Terminology

Participants reported that definitions and purposes of systems and models are sometimes too broad or vague, making them difficult to implement with fidelity. Explanations of systems and frameworks often include buzzwords without any specificities on goals, outcomes, and what effective implementation looks like with diverse student populations. This lack of clarity makes it challenging to measure implementation success, calling for a greater understanding on the purpose of the supportive system, who is involved in each moving piece, when implementation needs to begin, and what successful implementation looks like with diverse populations. The inconsistent understanding of these systems results in a lack of implementation fidelity, raising further concerns about whether or not these systems are implemented accurately and consistently.

Ideally, a comprehensive system of supports and data-management system work simultaneously, collaboratively, cohesively, and consistently to identify obstacles to student progress sooner rather than later, thereby helping keep students on track to graduate. However, fundamental flaws in implementation prevent schools from achieving their goal of improving graduation rates, particularly among those with disabilities.

Pave the Way to Success

Collaborative, Time-Conscious System Design and Improvement

Participants suggested focusing improvement efforts outside the high school context. The current structure emphasizes putting out fires rather than preventing fires. It is essential to consider our vast understanding of the interconnectedness and interdependence of the various stages of learning. A system of supports should span the continuum of an individual’s development and growth, starting in the pre-elementary stages and continuing to the post-secondary stages; this ensures a comprehensive focus on intervention and support before, during, and after high school.

Key players’ perspectives must be considered when designing new systems or making changes to existing ones. Educators, students, and caregivers are at the core of the systems we create and implement. Bridging the gap between research and practice entails bridging the gap between those who make systemic decisions and those who implement them. The traditionally hierarchical system, in which everyone works in isolation and in fear of authority, needs to be replaced with a collaborative system in which all constituents have a say in what occurs on the pathway to student success. These voices must be at the forefront of the decision-making table, including more intentional involvement in IEP meetings (beyond what is required by law). IEP information dissemination and decision-making must intentionally include caregivers and students with accessible and approachable language. All key players’ voices must be respected so that the entire team can work in unison to implement programs through a holistic lens.

Barrier

Constantly Reinventing the Wheel without Proper System Training and User Assessment

Fidelity of implementation has long been an issue in the classroom and fidelity and accountability go hand in hand. Educators shared that they were overwhelmed with systemic changes and requirements, never truly mastering best practices in monitoring systems-level growth and stagnation and making appropriate decisions around these observations.

Pave the Way to Success

Accountability & Fidelity

Participants spoke of the need for greater clarity on successfully implementing an effective, comprehensive system of supports. They stressed that the issue of accountability and fidelity could be addressed with the following:

- Intentional teacher training about effective system implementation and

- Understanding of effectiveness metrics for measurement

This calls for a need for better teacher training, a better understanding of who is responsible for each moving part of system implementation, and third, and a rubric-based continuous evaluation process to ensure that the system is implemented and revised consistently across districts and across time. Continuous progress monitoring is essential for evaluating students, educators, and systems implementation progress.

Concluding Thoughts

The imbalance in graduation rates between students with and without disabilities is alarming. The phase 1 and 2 focus groups identified barriers to success and pathways for change in order to address issues surrounding changing mindsets, building knowledge, and implementing effective systems. The next phase is to take action on these findings. Moving forward, education leaders must create a better system that ensures that students receive appropriate and timely services and accommodations across age groups, schools, and settings. The solutions to these challenges lie in a deeper understanding of and resulting change in the following:

- the type of language and cultural lens used when addressing student strengths and needs,

- the skills, knowledge, and voices considered at the decision-making table, and

- the overarching systems and processes school systems implement in the name of student success.

Our education system can bridge the gap between expectation and reality, knowledge and practice, and siloed systems and constituents through community, voice, and action.

Acknowledgement

We want to thank our partners and members of NCLD’s young adult leadership council who helped create and review content, recruit participants, aggregate data and information, share their stories, and provide feedback on the full report. We appreciate everyone’s insight, expertise, and passion for disability advocacy.

Members of NCLD’s Professional Advisory Board:

Dr. George Batsche

Dr. David Chard

Dr. Bambi Lockman

Kristen Hengtgen

Claudia Koocheck

NCLD Partners:

Stacey Labit-Moorehead

Beth Hardcastle

Dr. Shae-Brie Dow

Dr. Tessie Bailey

Amy Peterson

Dr. Amber Humm-Patnode

Dr. Erica Lembke

Members of NCLD’s Young Adult Leadership Council:

Amy Mabile

Athena Hallberg

Cassidy McClellan

Erin Crosby

Jocelynn Dow

William Marsh

The GRAD Partnership:

Dr. Robert Balfanz

Tara Madden

Dr. Jenny Scala

Marie Husby-Slater

Maria Waltemeyer

Megan Reder-Schopp

Jeanie Stark

Endnotes

1 National Center for Education Statistics. (2023). Students With Disabilities. Condition of Education. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Retrieved [June 15, 2022], from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cgg.

2 A person with a disability has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities (Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990). Under federal law, students ages 3–21 with “an intellectual disability, a hearing impairment (including deafness), a speech or language impairment, a visual impairment (including blindness), a serious emotional disturbance, an orthopedic impairment, autism, traumatic brain injury, an other health impairment, a specific learning disability, deaf-blindness, or multiple disabilities” have a right to a free and appropriate education and special education and related services (Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004, §300.304–300.311).

3 Chapman, C., Laird, J., Ifill, N., and KewalRamani, A. (2011). Trends in High School Dropout and Completion Rates in the United States: 1972–2009 (NCES 2012-006). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. Retrieved [June 15, 2022] from https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/.

4 U.S. Department of Education Office of Civil Rights. (2014, March). Civil Rights Data collection, Data Snapshot: School Discipline. https://ocrdata.ed.gov/assets/downloads/CRDC-School-Discipline-Snapshot.pdf.

5 ibid.

6 Gregory, A., Skiba, R. J., & Noguera, P. A. (2010). The achievement gap and the discipline gap: Two sides of the same coin?. Educational researcher, 39(1), 59-68.

7 Chu, E. M., & Ready, D. D. (2018). Exclusion and urban public high schools: Short-and long-term consequences of school suspensions. American Journal of Education, 124(4), 479-509.

8 Robison, S., Jaggers, J., Rhodes, J., Blackmon, B. J., & Church, W. (2017). Correlates of educational success: Predictors of school dropout and graduation for urban students in the Deep South. Children and Youth Services Review, 73, 37-46.

9 Note that this document was prepared by the National Center for Learning Disabilities. As such, the discussions around disability were biased toward individuals’ experiences around specific learning disabilities (the largest proportion of students served under IDEA). A specific learning disability is “a disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding or in using language, spoken or written, which may manifest itself in the imperfect ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell, or do mathematical calculations…Specific learning disability does not include learning problems that are primarily the result of visual, hearing, or motor disabilities, of intellectual disability, of emotional disturbance, or of environmental, cultural, or economic disadvantage” (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 2004, §300.8(c)(10)). Approximately one-third of the 7 million students with disabilities served under IDEA in the U.S. have a specific learning disability; 12% of students with specific learning disabilities dropped out of high school in the 2019–2020 school year (close to the national average for all disabilities).

10 Students with specific learning disabilities often need targeted and intensive academic support to ensure they can access grade-level content. Without access, students often experience frustration and disengagement.

11 Doren, B., Murray, C., & Gau, J. M. (2014). Salient predictors of school dropout among secondary students with learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 29(4), 150-159.

12 Zablocki, M., & Krezmien, M. P. (2013). Drop-out predictors among students with high-incidence disabilities: A national longitudinal and transitional study 2 analysis. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 24(1), 53-64.

13 U.S. Department of Education, Office of Planning, Evaluation and Policy Development, Policy and Program Studies Service. (2016, September). Issue Brief: Early Warning systems. https://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/eval/high-school/early-warning-systems-brief.pdf.

14 The University of Utah, Utah Education Policy Center. (2012, July). Research Brief: Chronic Absenteeism. https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs/regions/west/relwestFiles/pdf/508_UEPC_Chronic_Absenteeism_Research_Brief.pdf.

15 Baker, R. S., Berning, A. W., Gowda, S. M., Zhang, S., & Hawn, A. (2020). Predicting K-12 Dropout. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 25(1), 28–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/10824669.2019.1670065.

16 Zablocki, M., & Krezmien, M. P. (2013). Drop-Out Predictors Among Students With High-Incidence Disabilities: A National Longitudinal and Transitional Study 2 Analysis. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 24(1), 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1044207311427726.

17 Uvaas, T., & McKevitt, B. C. (2013). Improving Transitions To High School: A Review Of Current Research And Practice. Preventing School Failure, 57(2), 70–76. Https://Doi.org/10.1080/1045988X.2012.664580.

18 Note that while NCLD focuses on advocating for the needs of students with specific learning disabilities, the two-phase inquiry addressed barriers to success for all students with disabilities (with a strong focus on learning disabilities).